Wednesday 5th February 1919

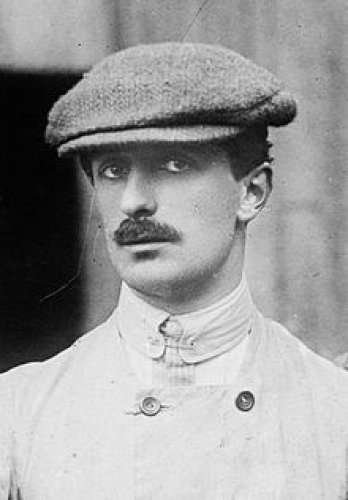

The first Voisin automobile was completed and test driven by Gabriel Voisin. Eccentric and iconoclastic, Gabriel Voisin was an aviation pioneer who sought to imprint his considerable ego on the world of automobiles. And why would he not have an ego? Wasn’t it he, and not those Americans, the Wrights, who was first to fly an airplane? Hadn’t his design for a V-12 pointed the way for Rolls-Royce to develop its own? Voisin’s creations were true mirrors of his soul, some of the most extreme, flamboyant, and aesthetically refined vehicles ever to move under their own power.

Voisin–the name translates as “neighbor”–was born at Belleville-sur-Saone, France, on February 5, 1880, the son of foundry engineer Georges Voisin. He studied architecture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in nearby Lyon, and landed a job with the Parisian architectural firm of Godefroy & Freynet, but his head was in the clouds–he was interested in flight. He left architecture to join Ernest Archdeacon, head of the Aviation Syndicate, and in 1904 joined his brother Charles and Louis Bleriot, who would go on to fame as the first man to fly the English Channel, in taking over the Surcouf Aviation factory at Billancourt.

When Bleriot left in 1907, the Voisin brothers established Voisin Freres in the Paris suburb of Issy-les-Moulineaux, the world’s first aviation firm. Voisin built an airplane that took off under its own power and remained airborne for 250 feet at a time when Wright’s planes needed a catapult to get aloft–leading to his claim to have created the first true flying machine. In 1909, at 29, he became the youngest knight of the French Legion of Honor.

The Voisins expanded their business, and succeeded in selling 59 aircraft by 1911, though Gabriel was greatly affected when Charles was killed the next year in a car crash. Fortune smiled in 1914, when Alexandre Miller, the French minister of war, chose the Voisin as the standard aircraft for the French air force. The factory was not big enough to meet demand, so his biplanes were built by other aircraft manufacturers, including Breguet and Nieuport.

When the Armistice of 1918 brought an end to the big aircraft orders, Voisin beat his swords into plowshares, turning his large factory and 2,000 employees to the production of automobiles. For his first car, named the C1 for his late brother, Voisin bought a ready-made design that had been turned down by Citroën because its 80hp Knight sleeve-valve engine had been deemed too expensive to manufacture. Eccentric or stubborn, once Gabriel Voisin had chosen the sleeve-valve design, he stayed with it through the end of production, paying Charles Knight a royalty on each unit.

Voisin tinkered with other ideas, including a 500cc cyclecar he called le Sulky, and the wildly experimental C2, shown at the Paris Salon of 1921. Its narrow-angle, 7.2-liter, V-12 engine was a masterpiece of complexity inside, but a minimalist triumph on the outside. Each wheel had its own closed hydraulic circuit, and the clutch consisted of two facing turbines in an oil bath. “It was too complex and therefore prohibitively expensive to produce in as small a factory as ours,” Voisin admitted.

The C1 was followed in production by the C3, with a high-compression engine producing as much as 140hp. Voisin offered a reward of 500,000 francs to anyone who could produce an engine of the same size that matched the Voisin’s efficiency and performance, and never had to pay out–no one took up the challenge.

Other models followed, including the four-cylinder C4, the car that beat the Orient Express from Paris to Milan, and the six-cylinder C11, the most commercially successful of all Voisin’s cars. He built three cars propelled by his V12L engine, an inline-12 that was two straight-sixes coupled end to end.

Despite his background in aviation, Voisin’s coachwork owed much more to his earlier career as an architect. His designs were light, but hardly could be considered aerodynamic, their odd angles, planes and curves owing more to cubism than the wind tunnel. In fact, Voisin maintained a friendship with modernist architect Le Corbusier, who designed the door handles on early cars and would later champion Voisin’s ideas for a planned industrial city.

Whatever his strengths as an engineer, Voisin was a poor businessman, and often showed his disdain for the typical motorist. His suggestion for those who criticized his cars was that they buy another make. He was contemptuous of American-style advertising that put emotion ahead of cold facts, and sneered at those who would swallow such advertising.

The Depression was hard on a company like Voisin that catered to the wealthy and the famous, and Gabriel Voisin lost control of his company in 1932, much like his countryman, Andre Citroën. Though he was able to regain it in 1934, he lost it for good three years later.

Voisin continued to create, designing an aluminum microcar called the Biscooter after the war, and exploring ideas for steam power. An odd, six-wheeled truck powered by a 200cc engine, shown at the 1958 Paris Salon, became the last car to bear his name.

He retired to Tournus in 1960 to write his memoirs, and received a steady stream of visitors, many of whom wanted to know about his rather extensive love life. (Separated from his wife, Adrienne Lola, in 1926, he married a Spanish girl of about 18 in 1950, and set up house with her and her elder sister, who “came as part of her dowry.”) He remained close to his daughter from his first marriage, Jeanne. Voisin wanted to talk about his place in aviation history, and showed no interest in his automobiles. “Why are you bothering with old crocks like that?” he asked a visitor who had arrived in a Voisin. “At your age, you should be spending your time and money on pretty girls.”

Voisin died on Christmas Day, 1973, and was buried in the village of Le Villars, not far from his birthplace.